History of the Aioli Dinner

Probably his most famous Cajun painting, the Aioli Dinner (1971, 32×46 inches) is George Rodrigue’s first painting with people. It is based on the old Creole Gourmet Societies, in their heyday between 1890 and 1920 when they met each month on the lawn of a different plantation home in and around New Iberia, Louisiana. The six hour meals included a lavish spread, cooked by the women standing along the back, served by the young men standing around the table, and enjoyed by the seated gentlemen, each with their own bottle of wine. The very French meal was not the Cajun cuisine one would expect. In fact, the men did not claim to be Cajun at all.They were French, and their cuisine was Creole.

(Although these definitions have taken on expanded meanings over the years, in nineteenth century Louisiana the term ‘Creole,’ as applied to a person, refers to someone of usually French or Spanish parents who was born in the Louisiana Territory before the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. The term ‘Creole,’ as applied to the food, refers to the cuisine of the French high society living in Louisiana. The term ‘Aioli’ refers to a garlic-butter sauce.)

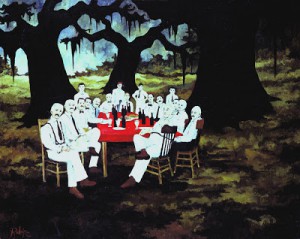

After three years of painting landscapes, George began to wonder, What would a person look like who walked out from behind one of my trees? He decided that they would be primitive, like the land.They would be a timeless resident. Is it 1800 or 1900? Perhaps they would be ghosts, floating and caught — by the trees, by the land, and by their heritage.

To capture this he broke numerous rules of art, the most obvious of which is his use of light. With his landscapes the light shined in the distance, underneath the trees. This continued in his Cajun paintings, but he began to look at this light with a broader symbolic connotation. He saw the light as the hope of a displaced people —–the hope for their future in a new world, in the swamps and prairies of South Louisiana. After the 1755 Grand Dérangement, the Cajuns thought they would be welcome in New Orleans. Yet New Orleans society could not be a home to these farmers, and so they traveled west on the Bayou Teche and made Acadiana their home, supporting the big city of New Orleans with cattle and crops.

You might remember from an earlier post that George’s mother never claimed to be Cajun. She was French. This is true of the members of the Creole Gourmet Societies as well. As late as the 1970s, the word ‘Cajun’ was considered to be a derogatory label among the French and Canadian settlers. A Cajun was poor and ignorant. A Cajun worked hard and lived off of the land. When George announced to his mother after completing the Aioli Dinnerthat he is a ‘Cajun Artist,’ she was offended and begged him to reconsider this label.

But George is proud of his Cajun heritage (as are thousands of Cajuns today), and his years of art school in California increased that sense of nostalgia. He saw his heritage fading before his eyes, unable to resist a modern world, and he strove to capture it ironically, with a contemporary and radical approach to art. In his words, he would “graphically interpret the Cajun culture on canvas.”

And so these people, the ones who walk out from behind a tree in a Rodrigue painting, are not hidden in the shadows of heavy branches and drooping moss, as one would expect. Rather they shine with an unnatural light; they are framed by the tree, their heads never touching the sky. They are cut out and pasted onto their landscape, just like they were removed from Nova Scotia and inserted into South Louisiana. Most importantly, in every Rodrigue painting the Cajun people glow with their culture.

In the six months it took him to paint the Aioli Dinner, George developed many of these ideas, and he honed his abilities as a portrait artist. His grandfather’s face alone took him three days. After finishing this painting, he moved forward as a different artist.

Ironically, after three years and hundreds of versions of landscape paintings, George wasn’t sure how to tackle the Aioli Dinner’s foreground. He was, however, confident in the design, dividing the canvas into a strong diagonal. I was surprised when I saw the original painting at how the ground treatment almost seems like an afterthought, as if George said, “Whew, I finally got through all of these portraits; now I can just knock out this grass.” The truth is that he had not yet found his comfort zone when it came to painting large areas of ground.

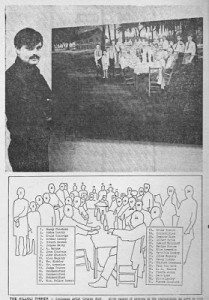

He chose the Darby House as the setting for his painting, because in his research of these Gourmet Clubs, it was the only one referenced that was still standing in 1971. The house was in bad shape (and has since burned down), but it was a grand estate in its day. In addition to George’s grandfather, Jean Courrege (seated front left, and looking at us), Octave Darby, the owner of the house, makes an appearance, as does George’s uncle, Emile Courrege (the young boy standing third from the left and cocking his head to the side).

It’s interesting to note that never at one time were all of these men at one meal together. George placed them that way, using a combination of photographs from various dinners. I guess it could be described as a dinner of ghosts. The only time they all got together was in George’s painted illusion.

The history of the painting itself, content aside, is also quite interesting. When George finished the Aioli Dinner in late 1971 he put a big price on it ($5,000, far higher than the several hundred dollars he was now charging for landscapes), because it took him six months, and because he knew immediately that he’d created something significant. It hung on the wall for sale in his gallery in Lafayette, Louisiana for fifteen years, and as he raised other prices, he raised this one accordingly. It was always the most expensive painting in his gallery. When the Zigler Museum in Jennings, Louisiana asked to borrow a Rodrigue for display, George pulled the Aioli Dinner off the market and sent it to this historic house in a small Cajun town, where it hung for more than ten years.

By the early 1990s the Blue Dog paintings broadened George’s appeal, and museums made regular requests. He loaned out the Aioli Dinner numerous times over the years, still not quite sure what to do with this painting, his Cajun masterpiece. Finally, about five years ago he gave the work to his sons, André and Jacques, and they placed it on permanent loan with the New Orleans Museum of Art, where it hangs most of the time today, currently on the walls of the balcony gallery with other American landscape paintings such as Asher B. Durand and George Inness.

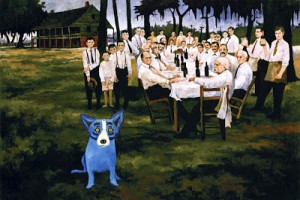

The Aioli Dinner has continued to inspire George over the years. He painted several versions of these dinner scenes during the 1970s and 1980s, and in 2001 he reinterpreted the scene with the Blue Dog, in Family Business for the Xerox Collection.

George made several print versions of the Aioli Dinner, but it was a problem from the beginning. The painting’s overall green tone lead to large black areas in early lithographs, and much of the subtleties were lost. Finally, in 1992 he tried a new approach. He created a 30×40 inch direct image transfer of the painting (essentially a photograph glued to masonite board). He then repainted the entire work on top in lighter and more contrasting tones, removing much of the green, and approaching the foreground with the confidence and skill that he developed over the previous twenty years. He photographed the re-worked piece and eventually (in 2003) used the new transparency to make a fine art silkscreen. The resulting print is far superior in color and clarity to the earlier versions.

Interestingly enough, George now found himself with an extra Aioli Dinner. He couldn’t resist including the Blue Dog (after all, it was as if he’d left room for it all those years ago). He called this ‘new’ original Eat, Drink, and Forget the Blues, a piece he made for his own collection, never translating it into print form.

The Aioli Dinner continues to inspire. In depicting one tradition, it encapsulates a unique and some would say dying culture, one that remained intact and isolated longer than most within America. In 1971 George Rodrigue set out to record this culture, to “graphically interpret Southwest Louisiana and the Cajuns,” and for the next twenty years that is exactly what he did. And yet I would argue that, even if he had changed directions after completing this one painting, he still would have met that ambitious goal.

{ Credit: Musings of an Artists Wife by Wendy Rodrigue, www.wendyrodrigue.com }